|

Our consultations revealed strong support for a clean start through the establishment of an entirely new peak body, with a democratic constitution and member participation, forward-looking outlook reflecting a maturing industry, and representative across the organic supply chain. Particular attention must be given to representative mechanisms that support accountability of institutions. We considered numerous options for new industry peak body and we tested aspects of these options in our consultations. We are strongly of the view that the widest possible range of organic operators should determine the structure of the peak body, as this would be a powerful mechanism to promote democracy in the industry. AOIWG should progress further consultations based on further development of the two most promising possibilities:

However, we have no doubt that the best outcome would be best achieved if Australian Organic, NASAA and the Organic Federation of Australia can reject the failed past attempts at collaboration, settle their differences, and merge their advocacy functions to form a new peak body. This would send a powerful message to the whole industry and external stakeholders that the industry is jettisoning its fractious history and focusing on unity and the future. |

The need to reform structures and processes

The current structure of organic industry bodies is a key factor in industry dysfunction. Critical accountability mechanisms are absent across existing advocacy bodies, and this contributes to the dysfunction.

Our consultations revealed strong support for a clean start through the establishment of an entirely new peak body, with a democratic constitution and member participation, a forward-looking outlook reflecting a maturing industry, and representative across the organic supply chain.

Reforming this structure and improving representative mechanisms are necessary preconditions to the industry uniting. Truly representational organisations are difficult to sustain in a nation as geographically dispersed as Australia. Particular attention must be given to representative mechanisms that support accountability of institutions.

- Annual general meetings are especially problematic, as they tend to involve a relatively small group of motivated participants who may not be adequately representative of the broader industry.

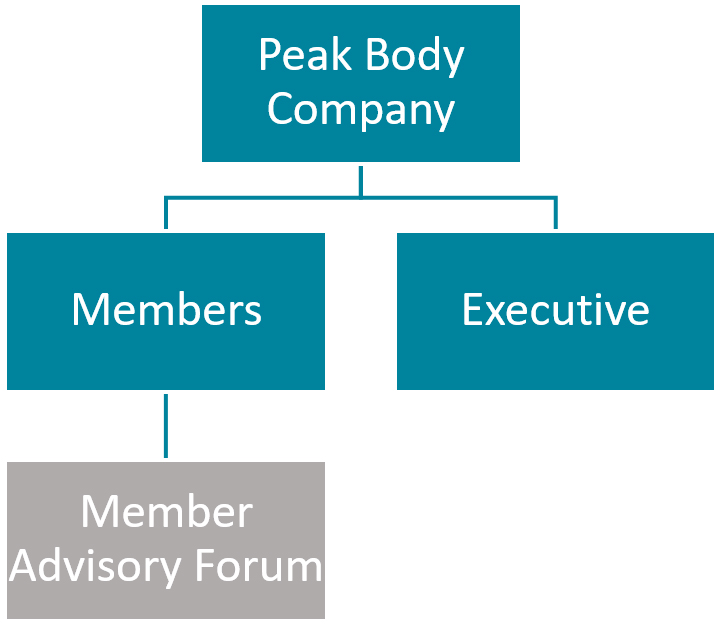

- There needs to be a clear delineation between:

- the membership, which must be provided with a range of opportunities to set the strategic direction and policies of the peak body; and

- an executive, which needs to run the operations of the peak body professionally and effectively, but in line with the strategic direction set by the membership

- Strong accountability mechanisms are critical, so the executive is clearly accountable to the membership for operational efficiency and its effectiveness in achieving strategic outcomes.

There are, broadly, five elements of structure that need to be considered.

- What legal form should the peak body take?

- Who should be the members of the peak body and how are they organised?

- Is an executive required and how is it accountable?

- Where should organic standards be located and made accountable?

-

What is the relationship of the peak body to the certifiers?

Above all, it is necessary for a representative body to keep asking critical questions about who it is representing. In this case, it would something like, “how do we ensure we are truly representing the interests of producers, processors and traders”?

Principles for assessing options

Clear principles are needed to guide the design of structural options and to provide adequate assurances for those who need to sign up, or sign over, to the new entity.

Throughout the consultations, participants were asked about relevant criteria for assessing the options. They were asked 'What are the key success criteria?' defined in terms of what they thought would work and has a high probability of success.

More detail on the principles we endorse for the organic industry in designing good governance to support high levels of performance is at Attachment D. The following is a summary of the key points for the organic industry.

Constituted to represent the full spectrum of industry interests

Peak bodies should have a clear mandate, charter and constitution. Any peak body for organics must be constituted to represent the full supply chain spectrum of organic industry interests from consultants and input suppliers, growers, processors, exporters, wholesalers, retailers and certifiers.

Open, transparent and democratic decision-making

For a peak body to win trust and confidence, and to be trusted as representing the majority of the industry, there must be open, transparent and democratic decision‑making processes. These processes need to be fair and seen to be fair. Confidence and trust will be eroded if there is a sense that an inner group is making the important policy decision behind closed doors.

Successful organisations work out how to have sound, democratic and open processes for key policy, strategy and financial decisions while also managing delegations in respect of these functions to their professional staff, board and executive.

Capable of inclusive policy development and effective advocacy

The way in which national policy is developed and agreed should be open and subject to both scrutiny and participation by all members before being advocated openly.

Robust debate on policy platforms within the industry is healthy, but debate or conflicting messages outside the industry is unhealthy and potentially calamitous in respect of both the key policy issue and the industry’s credibility with external stakeholders.

Generally, peak bodies have a clear processes and protocols on who can speak on behalf of the organisations. They usually have a governing board, sometimes a wider industry council, and established policy positions and ways of reaching broad industry positions.

Designed for good governance

Corporate governance involves a set of relationships between a company’s management, its board, its shareholders and other stakeholders. Corporate governance also provides the structure through which the objectives of the company are set, and the means of attaining those objectives and monitoring performance are determined.

Poor governance can be fatal for organisations and its leaders. Good governance matters in terms of legality, credibility, probity and respectability of an organisation’s actions.

Operates legally and with efficient bureaucracy

Organisations must have a minimum set of bureaucratic processes in place to meet legal requirements and good corporate governance standards. But, while bureaucracy can assist an organisation avoid poor performance, too much bureaucracy can impede strong performance—there is a need to strike the right balance for any organisation’s unique operating environment.

Generates value and is financially sustainable

A new peak body must have strong and widespread support, a compelling business case and engender confidence in its ability to generate value. Clearly articulating how the peak body will generate value to the industry, to its members, funders and supporters is critical to engendering confidence.

Engenders trust and goodwill and is widely supported

A peak body must have sufficient support from its members and stakeholders. To be successful, the organisation should be able to bring protagonists together, through inclusive processes, rather than alienating key actors.

Enables regeneration of leadership

Throughout the consultations, there was a commonly expressed refrain about the need for a new generation of industry leaders to drive the industry and its organisations into the future. It would be timely for a new or revitalised peak body to enable a new generation of industry leaders to make a fresh start. Ensuring a balanced transition from experienced hands to new one is a tactical concern of those directly involved.

Organisational functions and priority setting

The consultations identified support for the typical functions of a peak body such as:

- articulating a whole of industry vision and the setting of priorities

- developing policies and position statements and advocating them

- developing and articulating research and development priorities and strategies

- influencing and engaging with research development corporations (RDCs) and researchers

- industry development support

- industry oversight and compliance

- education, professional development and training

- industry development and marketing, including export market development

There was no disagreement that these were the types of functions that an organic industry peak body should participate in. However, there were two main issues of contention as to the policy issues which these functions should be applied to:

- there were disparate views about whether the peak body should be involved in standards

- domestic market regulation and integrity were viewed as a high priority

There was a low level of recognition that these two issues are inextricably linked and, therefore, it would not be fruitful to pursue improved market integrity without tackling improvements in regulatory arrangements.

Our view is not so much “which functions” should be undertaken (we agree they all should), but rather what are the relative priorities and, over time, how these are determined and how much resourcing should be allocated and reallocated. These are matters of the governance processes and structures and the decision rules engendered by the constitution and procedures of the entity.

Legal structure of a peak body

We considered numerous options for a new industry peak body and we tested aspects of these options in our consultations.

A. Revitalisation of Organic Federation of Australia

Our initial view was that revitalisation of the existing peak body was the logical and likely contender. OFA has been established for more than two decades, has a broad mandate and some existing structures in place, and has some successes in respect of market access, the development of AS6000, development of the national marque, its relationship with the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements, and its preparation of a bid to host the Organic World Conference in 2020.

However, the OFA has struggled financially and has minimal existing capability—few assets, negligible intellectual property, no significant revenue stream, no staff, absence of strategic alliances with other sectors and RDCs, lack of democratic policy development—and our consultations revealed it has significant reputational problems and lacks support from key industry players. In fact, some of those consulted were categorical that the OFA would never garner broad industry support.

B. Merger of existing industry bodies

This option would involve the demerger of the non-certifier functions and resources of Australian Organic and NASAA, and their merger with OFA to form a new peak body.

Both NASAA and Australian Organic have been involved in delivering some of the functions proposed for the peak body. There is the prospect of one or both demerging their certification functions and merging their advocacy functions with the OFA to form a new peak body that is focused on representing the industry. The reconstitution required is major in order to permit an opening up to all parts of the industry, including other certifiers. In plain language, the newly constituted organisation could not be a closed shop or club, but would need to be open to all parties, including other certifiers, who have a legitimate claim to representation in the industry.

This option would likely have broad support across the industry, provided the new body incorporated strong democratic processes and was open to all organic operators and certifiers.

If done well, this option has the advantage of involving less operational and financial risk than a new peak body; however, it does involve some reputational risks and requires member support for the merger.

C. Joint venture entity between existing industries bodies

This option is potentially useful as an interim measure prior to the full implementation of Option B. We envisage that Australian Organic, NASAA and OFA would form the nucleus of the joint venture in the first instance, but participation would be open to other entities as well—for example, larger operators and other certifiers.

However, the joint venture would involve a new body corporate, and therefore doesn’t have any operational or establishment advantages compared with creating a completely new peak body.

Nevertheless, this option could become very attractive if a temporary partner were to intervene to provide additional, temporary capability or seed funding—for example, a government, a large organic operator, or an RDC.

D. Australian Organic

This option emerged during the project and is being promoted by Australian Organic. It first requires the full de‑merger of Australian Organic Ltd (AOL) and its wholly owned subsidiary certifier operation, Australian Certified Organic Ltd. Being no longer a certifier, AOL would then emerge as the peak body.

There are some advantages in this option.

- AOL asserts that it already has around 1,000 members, which is perhaps a third of organic operators.

- AOL has built up strong financial reserves through its certification operations. If these financial resources vest in AOL rather than ACO, this would provide significant seed funding for the new peak body.

- Establishment risks are minimised because of the strong starting balance sheet, but also because AOL would have existing corporate structure, staff, marketing, business processes, and so on.

- If the “bud logo” vests in AOL rather than ACO, then there is potential for the logo to replace the national marque and provide a strong source of licensing revenue to support the provision of peak body functions.

However, there are also some drawbacks.

- It’s uncertain whether AOL members will support the demerger—particularly whether members will support the effective transfer of substantial financial assets from effective ownership by the certified operators (who contributed those assets), including the “bud logo”, to a peak body.

- The proposal does not currently promote improved representation across the industry (although any operator would be able to become a member of AOL—as they currently can).

- AOL has strong marketing capabilities, but has no particular expertise in policy development or advocacy—core capabilities for a peak body. It is possible that the existing corporate culture will undermine the development of effective policy and advocacy capabilities.

- AOL is based in Brisbane and, as the objective would be principally to influence national policies and stakeholders, normal practice would be for the peak body to be based in Canberra.

- Most importantly, the AOL proposal risks further divisiveness in the industry. Our consultations revealed some issues of trust in AOL across the industry and with external stakeholders, and particularly from organic operators aligned with certifiers other than ACO. This is largely a consequence of decades of AOL (via its predecessor, Biological Farmers of Australia) being a protagonist in the industry’s ‘squabbles’.

This last point is crucial and is an interesting prism through which to view options A through D. Option B should be preferred of these options for one highly symbolic reason. If AOL, NASAA and OFA could reject the failed past attempts at collaboration, settle their differences, and merge their advocacy functions, then this would send a very powerful message to the whole industry and external stakeholders that the industry is jettisoning its fractious history and focussing on unity and the future.

E. New peak body

Our consultations revealed strong support for a clean start through the establishment of an entirely new body. Participants supported a democratic structure, with tiered membership fees reflective of the turnover of businesses, a Board renewal policy and a members’ advisory forum. The consultations revealed broad satisfaction with the corporate structure of the seafood industry’s new peak body (Attachment C).

Perhaps the main reservation expressed about this option is that many organic operators consider that they already pay more in certification fees than they derive in benefit, and so any financial contribution to a new peak body would need to be offset by reductions in other fees—the industry development levies of AOL and NASAA are obvious considerations.

A new peak body also involves establishment risks that aren’t as pronounced in some of the other options, but this is substantially outweighed by the absence of reputational risks compared with other options. Importantly, the establishment of a new peak body could be a very positive statement about focussing on the future, and it also becomes more viable if other options become untenable.

Summary of peak body options

It is critical that organic operators determine the structure of the peak body, as this would be a powerful mechanism to promote democracy in the industry. We propose that the industry should progress further consultations based on further development of the two most promising possibilities—Option D and Option E.

Membership and democracy

Notwithstanding the chosen peak body vehicle, a clear finding from the consultations was a strong desire for better forums to improve representation and discuss policy.

Member advisory forum

There was support for a member advisory forum, along the lines of that adopted by the seafood industry, as an adjunct to the peak body. The relationship between the forum and the peak body will depend on the model chosen for a peak body, but it is envisaged that the forum would provide broad-based industry policy advice—for example, through the development of policy platforms—and the peak body would support the forum and operationalise the policy platforms.

There was support for a member advisory forum, along the lines of that adopted by the seafood industry, as an adjunct to the peak body. The relationship between the forum and the peak body will depend on the model chosen for a peak body, but it is envisaged that the forum would provide broad-based industry policy advice—for example, through the development of policy platforms—and the peak body would support the forum and operationalise the policy platforms.

In the case of the seafood industry, a member advisory forum is open to all members and held annually, in conjunction with the annual general meeting. These forums provide an opportunity for members to voice their thoughts on key issues facing their individual sectors and the larger seafood industry. This advice and comment will assist the seafood peak body to prioritise its action plan and establishment of policies. The member advisory forum is convened the day prior to each board meeting, with the location of each board meeting rotating between capital cities.

Three benefits from having such a forum include:

- addressing the absence of a mechanism for developing a broad range of policy—that is, focussing time, effort and dialogue on strategy and policy development, that is not just confined to organic standards

- providing an important networking forum for exchange of industry development information, growing the commercial and political ecology of the sector

- creating a source of creative tension between the members and the executive of the peak body—in this context, the executive could represent a Board appointed by the membership or executive staff; but either way, the executive is appointed to run the peak body

If conducted successfully, such a process may enable network members to develop a shared understanding of the policy problems in question, reach agreement on new and innovative solutions to policy problems, develop trust among network members, and assist members to learn about their interdependencies in pursuing their shared policy objectives. They would also become more informed advocates in the circles they move in and on social media, expanding the networks and influence.

Note that this model is an adjunct to a traditional model of accountability. The executive is appointed at an annual general meeting and is held to account through that process. The member forum will be effective only as far as the executive adopts and implements the strategies developed. If accountability is weak, it is possible that the executive will pursue its own strategies, which may be different to that of the membership—in fact, this misalignment between executive direction and member expectations is a problem that plagues many agricultural peak bodies.

Member council

A member council is a very different proposal to a member advisory forum. The purpose of a council would be to empower members more than would otherwise occur.

A member council is a very different proposal to a member advisory forum. The purpose of a council would be to empower members more than would otherwise occur.

The basic idea behind a member council is for the members to vest governance power in a large sub‑group of members that is more representative of the industry than could be achieved by simply appointing a Board. It also provides additional degrees of freedom to appoint outside specialists to the Board for operational objectives, without undermining industry representation. The main role of the member council would then be to set the strategic direction and hold to account those who implement that strategic direction.

Critically, it would be the member council that appoints the executive (and can replace it at any time), and they would invest more resources in continuous monitoring than is typically achieved through a normal annual general meeting.

There is a wide range of options to consider in structuring the member council. The most important parameters are:

- whether a Board is appointed to oversee the staff—in which case, the council will focus on policy development—or whether a CEO is directly accountable to the council—in which case, the council needs to also operate similar to a Board, by convening governance committees so the staff are accountable to the council

- what role the council and the annual general meeting play in appointing the executive—for example, whether:

- the council appoints the executive—in which case, what role would be served by the annual general meeting

- the executive is appointed by the annual general meeting—in which case, whether the council should play a role in recommending nominations to the executive

- how many members are appointed to the council, the frequency and mode of meeting, and the extent to which the peak body meets their costs of meeting

- whether the council is elected directly by the whole membership or whether there are chambers which appoint or elect members to the council —chambers could represent a sub‑group of the industry and may be based on commodity, geography or supply chain; for example, there could be chambers for:

- suppliers, growers, processors, traders and exporters

- beef, grain, health & beauty, horticulture and dairy producers

- states or regions

- the activities the council should be involved in

We suggest that the member council would be appointed for a two-year period and that the proposed biennial conference (see below) would occur mid‑term and be one focus for the council’s attention.

We have formed the view over the course of this project and through our consultations, that industry unity will be unlikely to coalesce unless a strongly representative forum, such as a member council, plays the preeminent role in enforcing accountability, setting strategic direction, developing policy platforms and resolving disputes (within the industry forums rather than in public).

Other mechanisms for advancing member democracy

Biennial conference

Many people told us that there were insufficient opportunities for organic operators to network, share experiences and debate issues. A biennial conference or industry summit would address this need.

Given the geographic dispersion of organic operators and the resources required in organisation, an annual conference may be too burdensome on participants and organisers. However, a conference convened every two years, where significant effort is put into organisation and topics, would likely be popular among the membership. The conference should have activities held over two days (plus some additional options—like tours of farms or processing works) to make it worthwhile for those who travel far.

One possibility would be to convene the first biennial conference in early 2018 with the focus of the conference being twofold:

- to bring as large an industry representation together as is possible and workshop the required industry structures

- to consider options for the future regulation of the industry—in the context of the review of arrangements under the Export Control Act (see Part 4)

Roadshow

Following in the tradition of the regional conferences held annually by the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, the organic industry could host a regional roadshow in conjunction with its biennial conference.

The roadshow could feature selected presentations and workshops from the national conference, as well as activities tailored to each location.

Regional networks

There are a small number of regionally organised networks of organic producers. These networks play a valuable role in providing peer support to organic producers, as well as being a forum for the promotion of organic methods and the discussion of key industry issues.

The peak body should consider how best to support these networks and to facilitate the creation of additional networks.